Ostracized to the margins of history, minority voices have often been muted. Drowned out by the victors’ version of events, the nuances presented by varied perspectives is missing from history books. But Helmerich Center for American Research’s inaugural Duane H. King Postdoctoral Fellow, Travis Jeffres, is working to provide a megaphone to indigenous people who migrated from central Mexico to northern Mexico and the U.S. Southwest hundreds of years ago.

Ostracized to the margins of history, minority voices have often been muted. Drowned out by the victors’ version of events, the nuances presented by varied perspectives is missing from history books. But Helmerich Center for American Research’s inaugural Duane H. King Postdoctoral Fellow, Travis Jeffres, is working to provide a megaphone to indigenous people who migrated from central Mexico to northern Mexico and the U.S. Southwest hundreds of years ago.

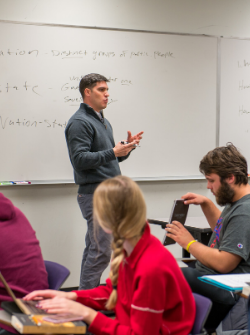

For one year, Jeffres will delve into the Hispanic documents, 25,000 pages of manuscripts housed at HCAR, while also teaching history classes at The University of Tulsa. “It’s really a dream position for me,” Jeffres said. “It gives me time to research and write, but I also get to teach and be at the epicenter of this amazing collection that is really helpful and useful to me.”

Gaining a new perspective

Jeffres is writing a book originating from his doctoral thesis with the working title The Mexican Indian Diaspora in the Great Southwest. By retracing the steps of the Spaniards and their allies from 1550 to 1680, he discovered compelling narratives that would make any historian’s eyebrows raise in curiosity.

“I started noticing these references to Nahuatl-speaking people, specifically the Tlaxcalans, who were allies of Hernán Cortés who overthrew the Aztec Empire,” he explained. “I am trying to figure out why these Nahuatl-speaking peoples, who were formerly restricted to central Mexico, ended up 1,500 miles away.”

In preparing his research, Jeffres not only mastered Spanish but he also learned to read Nahuatl. His ability to decipher the many texts written in Nahuatl revealed a more refined view of the Tlaxcalans and other Nahuas. The Tlaxcalans were seen as loyal allies of the Spaniards throughout the 16th century, but that may not be the entire story.

A last will and testament from a Tlaxcalan man, Domingo Morales, sheds light on a native person’s perspective when faced with colonizing the north. “Domingo says explicitly, ‘I have to prepare my soul in case I die where I have been chosen to be sent.’ In truth, he was terrified to go,” Jeffres shared. “For that one document alone, HCAR was incredibly important to my research.”

A globally minded classroom

Jeffres does not believe in shallow interpretations of history, and in the classroom, he challenges his students to think beyond their own borders. “If we can give people a historical perspective and encourage them to look at other cultures and see the value in them, it doesn’t make sense to study history according to nation states,” he added.

In the spring, Jeffres will bring his personal expertise to the classroom through a course at TU that focuses on diasporas, migration, identities and colonialism. The topic provides a learning opportunity for students to view the humanitarian crisis at the U.S.-Mexico border through the lens of history.

“People have been going back and forth over this imaginary line at the U.S.-Mexico border for thousands of years. These migrations are foundational to their identity, and we have forgotten that,” he said. “Historical insight encourages people to be more globally minded, which can translate into more inclusive notions of citizenship, nationhood and belonging.”

Historian on a mission

By dusting off and re-examining the stories of the 16th century Spanish conquest, Jeffres revealed a more complex story. “If we limit ourselves to only European sources, we are only going to see one side of the narrative,” he said. “Spanish colonists were not in the business of recording the thoughts, ideas and motivations of people that were subordinate to them under colonialism.”

Jeffres uses archival material as a front row seat to history, and he hopes others will pull up a seat.