By Travis Jeffres, Duane H. King Postdoctoral Fellow

By Travis Jeffres, Duane H. King Postdoctoral Fellow

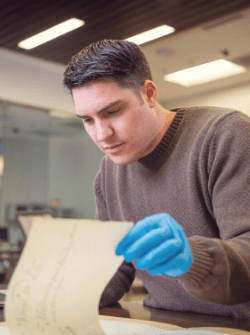

As a post-doctoral fellow at the Helmerich Center for American Research, I work primarily with the Hispanic Manuscripts — a 25,780-page collection of singular importance for the history and cultures of the Americas. But there is more to this collection than just Spanish-language documents. There are also materials written in Nahuatl — the language of the Aztecs and their neighbors. Before the conquest, Nahuatl was written pictographically, but early in the colonial era Spanish priests taught Native boys to write their language using the Latin alphabet. The tradition flourished, producing paper trails for historians to follow.

The Nahuatl materials at the Helmerich Center have been essential to my research. My current book project explores Native American allies’ involvement in the Spanish conquest of northern Mexico and the U.S. Southwest during the early colonial period. As part of this effort, in 1591 the Spanish colonial government resettled nearly 1,000 central Mexican Natives to the war-torn northern frontier. In the literature, these people have been portrayed as eager participants and willing volunteers. But a Nahuatl document written by a Native colonist flatly contradicts this narrative. In his last will and testament, written on the eve of his departure for the North, Domingo Morales wrote, “Even though I am not sick, I must prepare my soul in case I die where I am selected to be sent.” An alternate translation might read, “in case I die where they are sending me.” Setting this testament alongside other Spanish and Nahuatl documents, I reframed the 1591 mission as a coerced resettlement that rocked an indigenous community and tore Native families apart. In brief, the Nahuatl materials at the Helmerich Center allowed me to approach an imperial project from the perspective of indigenous “allies” whose motivations and experiences have been fundamentally misrepresented.

The majority of colonial Nahuatl documents are classified as “mundane texts” because they record the everyday affairs of local Indian communities, mostly in Mexico’s Central Valley. The Helmerich Center’s Nahuatl materials are no exception in this regard. However, the texts are far from mundane or ordinary. Morales’ will is the only document known to exist that provides insight into the 1591 resettlement from a participant’s perspective. And since colonial ventures were almost invariably documented in European languages, counterbalancing those accounts with indigenous perspectives is essential.

The Helmerich Center’s Nahuatl manuscripts are notable in other ways, too. Hispanic Manuscripts 107, for instance, contains a Nahuatl petition sent to the Spanish viceroy on behalf of the cabildo (municipal council) of Xochimilco, in modern Mexico City. The cabildo complains of houses being damaged or destroyed during the construction of a road that is being built through his territory. The Spanish built Mexico City atop the ruins of a razed Aztec Tenochtitlan, a feat that required an incredible amount of excavation, dredging and construction — much of it performed by and dramatically affecting indigenous communities. Far from recounting an unremarkable, everyday transaction, the Xochimilco petition offers a poignant glimpse into one community’s reckoning of the social costs of empire building in early colonial Mexico.

In addition to wills and petitions, there are also property deeds and descriptions of estates. In one 16th-century example, an indigenous drawing demarcating property boundaries — a map — appears on Native maguey paper.

Might the Nahuatl materials in the Hispanic Manuscripts Collection at the Helmerich Center yield additional unique finds — or even groundbreaking discoveries? There’s only one way to find out.